Ever been curious about how the Guide Rouge—the Michelin Guide—became the last word in gourmet dining around the world? Well, so were we. So we did some research to get to the bottom of what makes the little red guide so special (quite a lot, as it turns out) and caught up with the chef of a newly-starred restaurant here in Geneva to find out what the star means for restaurants and chefs—and what it changes.

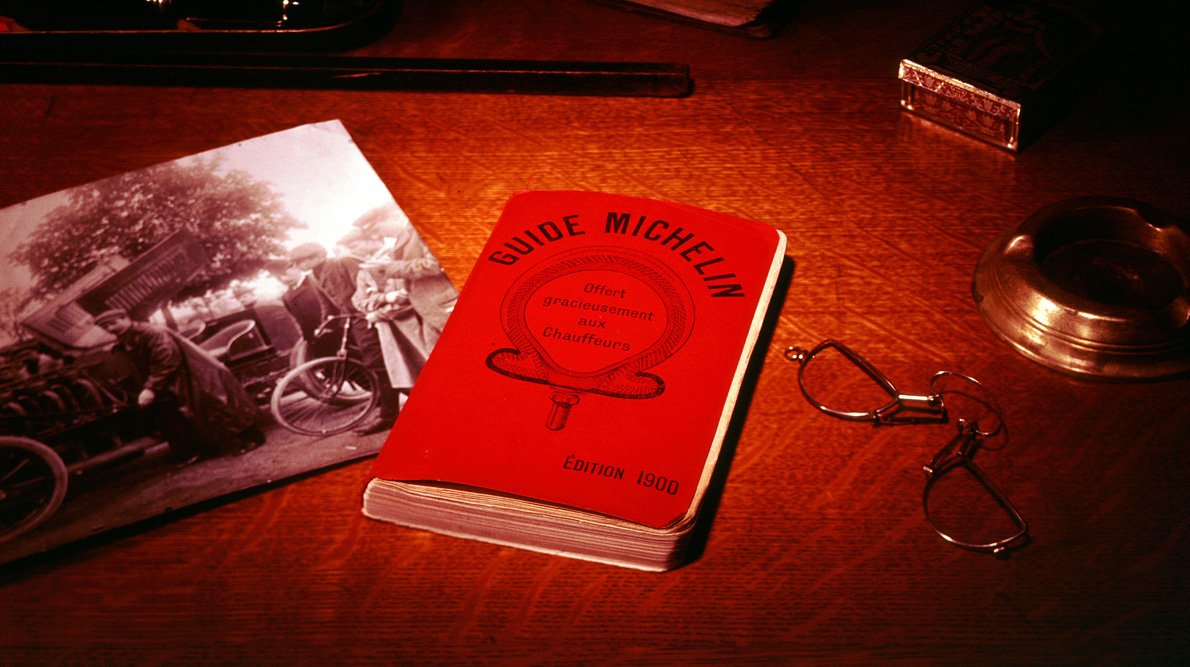

Let’s start with the fact that the Guide Michelin was originally conceived by brothers André and Edouard Michelin not in the name of gastronomy or even tourism, but simply as a way to sell tires. A 400-page first edition was hastily compiled and edited just in time for the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris, released with the sole purpose of getting French drivers into their cars, out on the road, driving between towns—the bankable theory being that they would eventually need to buy new tires. While other tourist guides at the time targeted the rail traveler exclusively, part of the Guide Rouge’s allure was that it pointed out some places that remained unserved by train. At the time, there were less than 3,000 registered automobiles circulating in France, so it was quite a gamble to produce 35,000 copies of a guide specifically targeting drivers—especially one that would be offered free of charge. It almost sounds silly, like sponsoring exercise to sell more food, but it worked: the guide became popular quickly, with a Belgium guide appearing in 1904, followed by Spain and Germany in 1910. Other European countries followed as Michelin become synonymous with unbiased reviews.

So, what information did that original red guide have inside? In fact, it was mostly a technical resource for drivers, complete with road maps, an alphabetical listing of all towns in France, the distance between towns, instructions on how to change a flat tire, lists of hotels ranked by price, and precise locations of gas stations and Michelin tire retailers around the country. Restaurants starting getting their own entries only in later editions, but the star rating system exactly as we know it today didn’t make its official début until 1933.

Restaurants with an entry but no star are deemed worthy of a visit by Michelin by their very inclusion, and those with no entry are simply not recommended. Emphasis is on location and journey all expressly worded for the driver in mind. While today the frequenters of three-star restaurants around the globe might be more jet-set than auto-club. One thing is for sure: traveling for good food was made popular by the Guide Rouge. And Just like the world of tourism has gone global, so too has the guide. Today the Michelin Guide collection comprises 26 guides covering 23 countries on three continents. The guide first went online in 2001, and the first US guide—New York City—came out in 2005. Brazil saw its first Michelin coverage in 2015, when guides were released for the cities of Sao Paulo and Rio.

So who gets to be in the guide? Even if you’re only slightly familiar with the Michelin guides, you may have heard about its infamous inspectors, who frequent restaurants anonymously and rate them. According to a 2005 study by the Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, which restaurants end up with entries in the guide is determined by “a rigorously selected and trained team of inspectors.” The study also notes the independence of the guide: “Unlike some competitors’ versions, all meals and accommodations used by its inspectors are fully paid for by the Michelin organization.” Indeed, André Michelin started charging for the guide in 1926, no longer accepting paid advertisements from hotels, and the organization is quick to point this out still today.

According to Michelin, in order to remain 100 percent anonymous, inspectors never take notes while dining, and they strictly apply five criteria when rating a restaurant: The last of the criteria may just be the most important for restaurants earning a star or more. Although there does not seem to be an exact number of visits that an inspector pays to each restaurant they rate, they are visited several times by inspectors before a guide is released, according to Michelin in a 2009 article in The New Yorker magazine.

If an air of secrecy exists around the guide, it has everything to do with its inspectors, deemed “famously anonymous” by Michelin itself in a 2009 ad campaign. Inspectors are not typically allowed to speak to the press or reveal their identities, nor are they encouraged to reveal their profession to their families. In an October article in Vanity Fair, an inspector—during a call where the journalist was not able to see her or learn her name—quipped that being a Michelin inspector was like “the C.I.A., but with better food.” There has also been no shortage of controversy surrounding the guides over the years, with one inspector, Pascal Rémy, being asked to leave Michelin (and later sued by the company) after publishing a juicy tell-all on the guide in 2004 called “L’inspecteur se met à table” (literally translated to “The inspector sits down at the table” but meaning, idiomatically, “The inspector tells all.”) More scandalous talk surfaced in recent years when Michelin was accused of perhaps loosening its strict criteria to promote certain regions, notably Japan, where there are currently more 3-star restaurants than anywhere else in the world (30 in total in 2016). Despite it all, Michelin holds tightly and fiercely to its claim of unbiased work.

While the inspectors themselves remain cloaked in mystery, the process they follow in rating restaurants is made transparent by Michelin: each year, an inspector is assigned a different region that he or she covers for several months, following rounds prepared by the individual guide’s editor-in-chief. On average, inspectors travel 30,000 kilometers per year, eat 250 meals in restaurants and stay in 160 hotels. To get it all done, they are on the road three weeks per month, returning to the Michelin offices during the fourth week to present their findings and prepare their next trip. Official entries and stars are assigned and chosen in a collaborative manner during “star sessions” where inspectors, editors-in-chief and the Director of Michelin Guides are all present. When disputes arise—and they do—restaurants are revisited. The guide is then compiled with comments, updated maps and information, and by the time the guide is printed and has hit bookshelves, the inspectors are back on the road visiting restaurants and hotels.

For a chef, gaining a Michelin star can make a career, paving the way for further investment in their restaurant and brand. Conversely, losing a star can break it—by effecting negative changes to sales and profitability by up to 50 percent, according to Cornell. Stories of chefs chasing stars are fairly notorious in the cut-throat culinary world, with some chefs even going so far as to make the “Walk to Canossa”—a reference to King Henry IV humbling himself before the pope—meaning they go to Michelin directly to state their restaurant’s case. The pressure that exists for chefs to maintain their stars can be intense as well, and along with the various controversies mentioned above, there has been tragedy associated with the guide as well. As Vanity Fair reports, the 52-year-old French chef Bernard Loiseau killed himself when rumors began circulating that Michelin would remove one of his restaurant’s three stars. The article also shares that when celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay lost a star at his London restaurant, he reportedly cried, as did the staff at Daniel, chef Daniel Boulud’s New York restaurant, when it had one of its stars removed in 2014.

But newly-starred restaurants are immune to such stories of suffering and intense pressure, and simply find themselves reveling in the exciting news of their achievement. Geneva’s La Bottega restaurant opened in June 2015, just five months before Michelin announced it would be given one star in the 2016 Switzerland guide. The restaurant’s chefs, Paulo Airudo and Francesco Gasbarro, told Hosco that they learned the news of their star from a German food blog very early on the morning of October 7, and not directly from Michelin. A 6 AM post on the La Bottega Twitter account, written in both French and Italian, reveals their excitement: “Hourra! Notre première #étoile #Michelin à #Genève!” (Hurray! Our first #Michelin #star in #Geneva!”). Airudo notes that they tried to call Michelin to confirm the blog, but they were told they would have to wait until 12 PM to find out, the time of the guide’s official release. At noon they confirmed the official news and celebrated with a champagne toast with their staff and lunch guests.

For Airudo, who has lived and worked in 13 different countries over his 13-year culinary career, from the United States to Mexico to various European destinations, gaining a Michelin star seems to be just another box checked on his long culinary to-do list. In fact, La Bottega was his first venture as chef-owner. “I always worked six months or one year in a place. It was never my goal to open my own place. It was just my goal to learn.” Airudo explains that it was also not his explicit goal to earn a star, and that he was “surprised” by the news, but that he does recognize the guide’s incredible influence, especially in Europe. “Getting a star forces you to grow, and I want to grow,” he says, adding that he also wants to earn a place on the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list.

As proof of how much earning a star can change things for a chef and restaurant—and also of the highly competitive nature of the culinary world—he adds, “Now it is my aim to have two or three, simply because there are more to have.” The La Bottega chefs have also added some new culinary projects around Geneva for 2016 since their star was announced, hence the potential growth factor associated with earning a star. Indeed, since receiving the news in October, Airudo and Gasbarro have changed the La Bottega kitchen—there are now 16 chefs working under them in the 52-seat restaurant—and reduced the number of covers they serve on a daily basis, all without raising the prices on the menu so far.

But Airudo is quick to point out that La Bottega—which means “workshop” or “boutique” in Italian—is different than other Geneva restaurants, which makes their star even more special. “People here are surprised by what we are. What we offer breaks the rules here. We have a standard of honest, friendly and funny service—not stiff. There is a lot of fanfare around traditional Michelin places here, and I find that unnecessary. For us, it’s what’s on the plate. “A second star does not mean more luxury to me, it means where we are in terms of food.” Michelin, apparently, also found what was on the plate to be enough. Its short commentary praises, above all, the simplicity of the products and the preparation. Airudo agrees, calling it a “perfect review.”

Responding to a question about how gaining a Michelin star has changed his life, Airudo says, “Well my life has changed in that I have more work. I have more jobs to do. Less relaxation. But growing or not growing is a choice—a simple choice.”

10 MICHELIN TRIVIA

- Japan has the most three star restaurants, with 27 (stats from 2015 as the 2016 guide has not been released yet) As a comparison, in 2015, France had 26.

- There were 112 3-star restaurants in the world in 2015, so almost half of them were found in France and Japan

- Joël Robuchon is the most decorated chef, with 25 stars in 2015, although he held 28 at one point. Coming in second in 2015 is Alain Ducasse, with 21 stars. Both are French.

- Dining among the stars is not cheap! The world’s most expensive 3-star restaurant is Kitcho, located in Tokyo, serving traditional Kaiseki cuisine from chef Kunio Tokuoka. The average price per person for a multi-course tasting is between €500 and €600.

- Switzerland is the most Michelin-starred nation per capita

- The first US guide came out in 2005 for New York City, and was followed in subsequent years by San Francisco and Chicago.

- Sukiyabashi Jiro wins for most inventive/unexpected location for a 3-star restaurant: the 10-seat establishment serves award-winning sushi by 90-year-old chef Jiro Ono in a basement office attached to Tokyo’s Ginza subway station. A documentary, ‘Jiro Dreams of Sushi’ was produced about the chef and his sushi in 2012.

- Paul Bocuse’s restaurant in Lyon, L’Auberge Du Pont de Collonges, has held a three-star Michelin ranking since 1965, setting the record for longevity.

- In 1933, when the three-star system was introduced, 23 restaurants in France earned 3 stars. The first one in alphabetic order? Le Chapon Fin in Bordeaux.

- Bibendum is the official name of what is commonly known as ‘Michelin Man’ and the company’s symbol, made to look like a stack of tires. This comes from the Latin ‘Nunc est bibendum’ (now is the time for drinking.) It was meant to convey the thought that ‘Michelin tires will drink up obstacles in the road.’ The image was actually taken from a rejected poster by a French cartoonist for a Munich bar in 1898, the original large man in the drawing replaced by a stack of tires resembling a human in shape and stature.